What is Mark My Bird all about?

The science

“How fast, as a matter of fact, do animals evolve in Nature?”

In 1942, this question was asked by George G. Simpson in his book Tempo and Mode in Evolution, and answering it is a major motivation for Mark My Bird. This is because the rate at which species change over time (their ‘evolutionary rate’) is thought to play an important role in generating the biological diversity that we see around us.

Species traits are all of the physical and behavioural attributes of species, and might include things like the shape and colour of a plant’s flower or the frequency and pitch of a bird’s song. Changes in traits such as these are just one way in which organisms might vary in their evolutionary rate, and it is differences in these rates that determine how life varies within and between groups of related species, and from one part of the world to another. For instance, unusually high rates of evolution might lead to groups of species that are exceptionally diverse in the way they look or behave – just think of the variety of beak shapes in Darwin’s Galapagos finches.

Another way that organisms can vary in their evolutionary rates is in how fast new species arise (speciation) or die (extinction). Variation in rates of speciation and extinction are important because they determine how numbers of species wax and wane over time, and where species are distributed around the world. If the rate of speciation is high and extinction low then diversity (the number of species) will increase over time.

With this in mind, bird bills are a particularly interesting species trait as they can tell us a great deal about the origins and maintenance of biological diversity. This is because bird bills are adapted to particular diets and foraging techniques, and so can tell us a lot about the ‘ecological niche’ of species – the role an animal plays in its environment. If bill shape evolves quickly it could be that many ecological niches have been rapidly occupied, or perhaps that the diversity of available niches has dramatically increased. Either way, this provides the opportunity for the rapid birth of new species (well, rapid on a geological timescale at least!) and it is questions related to these ideas that the Mark My Bird project aims to help answer.

Why shape?

Standard measurements such as length, depth and width are typically used for studying living birds in the field. But bird bills are incredibly diverse in shape and size, varying in curvature and often with other odd features (casques, ridges, spatulas) that are completely missed by common measurements. Working with museum collections and 3D scanners means that we can go further and use methods that tell us about shape in much more detail.

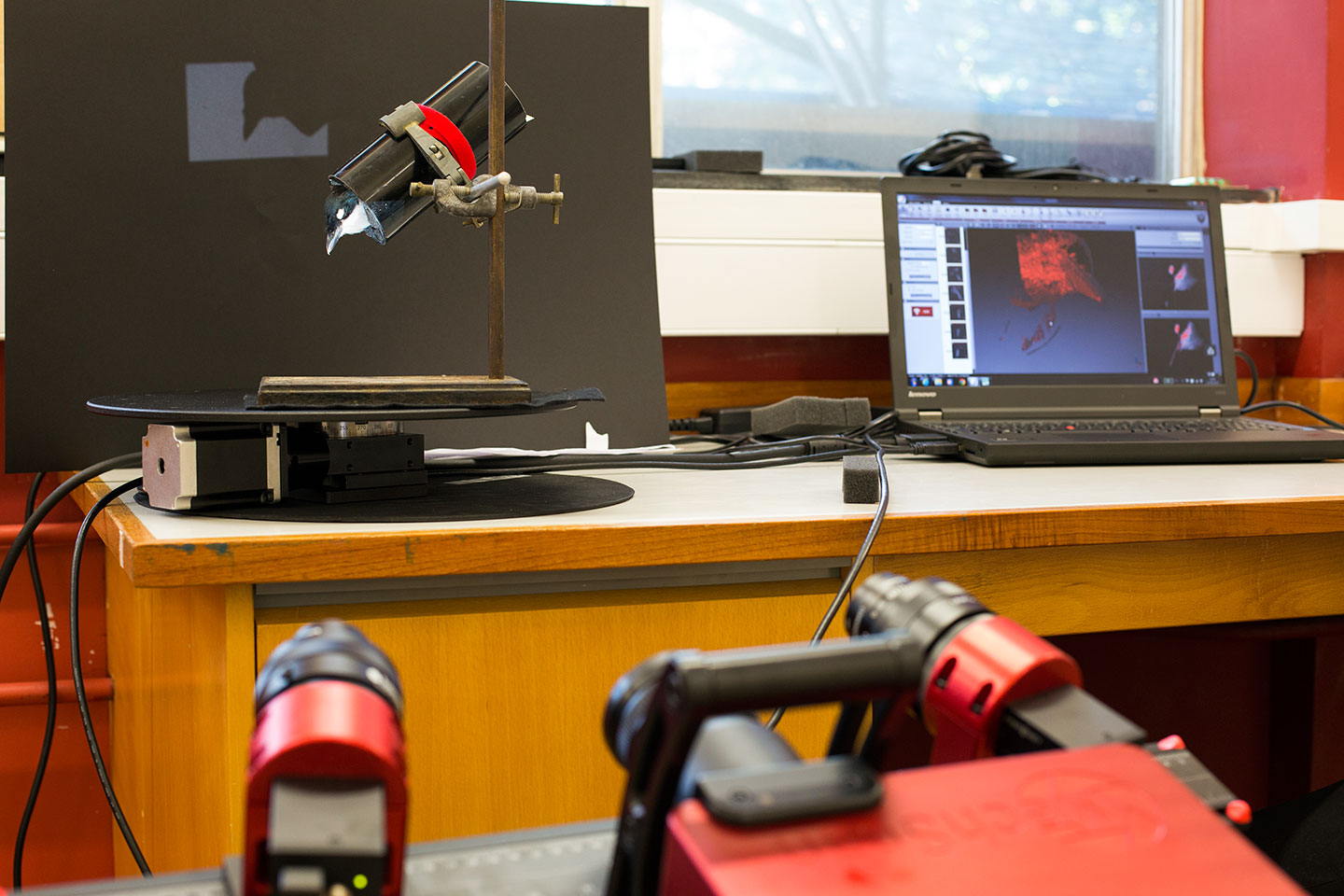

3D scanning

We are using 3D scanners to generate a model of each bird’s bill. These scanners shine either white or blue light onto the specimen, which is then photographed by two cameras. As the specimen is rotated, we take more scans, allowing us to create a 3D model. The model contains millions of 3D X, Y, and Z coordinates across the surface of the beak. Where the scanning ends, Mark My Bird begins - we move from accurate models of the bills to the quantifiable descriptions of shape that are critical to our analyses.

We are have three different scanners: HDI Advance R3X, HDI 109 and MechScan. The photos below feature the MechScan. It’s awesome.

Keeping up to date

We will highlight new research findings and outcomes on our research group website. You can also follow us on Twitter for more news and to take part in our weekly “guess the bird” competition #beakoftheweek.

Natural history collections

Measuring the size and shape of bills of all 10,000 species of bird is only possible by working with museum natural history collections. Museum collections are one of the greatest scientific resources available to us- what we see on display is a tiny fraction of the collections under the care of museum curators. These collections were largely amassed throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries from a wide range of sources- from voyages of discovery and admiralty expeditions to professional zoologists, collectors and amateur naturalists- as people began to explore, study and organise the natural world in a more systematic way. These wider collections now form an invaluable repository and catalogue of global biodiversity, preserved and utilised for research and education.

To date our data collection has been based in the ornithology collections at the Natural History Museum at Tring and at the Manchester Museum.

If you are interested in helping the Natural History Museum to transcribe the handwritten historical data for its bird specimens, please click here

What will happen to the data?

The data from Mark My Bird will be used not just by our team but will also be made publicly available, both for other scientists to analyse or develop and for anyone else who is interested to view and use. In the first instance we will submit our data, methods and analyses for publication in scientific journals. Once it has been subject to the rigours of peer review we will contribute our data to the Natural History Museum Data Portal. The Data Portal is a huge initiative by the NHM to digitize the ~80 million specimens in the Natural History collection. It is an Open Access resource so anyone can search and download the data. The value of natural history collections is increasingly widely recognised and we hope that we can contribute to the broader goal of opening up the seldom seen world of museum research collections.

Funding

All photos on this page taken by Chris Moody (centre and left images on the bottom row Copyright, Natural History Museum, London).